An ode to national cups

In an age of highly capitalistic football, cups are a romantic reminder of the bond between football clubs and local communities

One of my first, and most eye-opening experiences as a football anthropologist, doing fieldwork with Swedish-Kurdish team Dalkurd FF, was watching them play in the Swedish Cup. As they were in the 2nd tier of Swedish football, I had the opportunity to see them measure up against teams they would not play in the course of this season. During the group stage (unlike most countries, the Swedish league is divided into groups, and later a knockout-stage), they played two teams from the Allsvenskan (1st tier), and another one from a league below theirs.

Dalkurd FF x Djurgårdens IF. Photo by the author.

The match I witnessed between Dalkurd FF and Djurgården, reigning Swedish champions, in their rather cold and anodyne arena in Stockholm, ended up with a loss by 3 x 2. However, Dalkurd FF managed to put a good performance, specially during the 2nd half; a contrast to their defensive mistakes in the 1st half. Most of my informants mentioned that being able to play well against Swedish champions from a division above theirs was a good sign of the team’s grit and fighting spirit.

The oldest club competition in the world is a cup: the FA Cup. However, not only in England, but in most countries with professional football, the Cup is seen as a secondary trophy in comparison to the league and the continental trophies. In general, as football clubs began being founded all over the world, the need for constant play would ensure that the league format would be the most prestigious mode of competition. Not only would the format guarantee more competitive games, but they would reward teams that would be more consistent. More often than not, those teams would be grouped in relation to their skills, with a flow of the best teams from lower divisions, replacing the worst from the higher divisions. In a league game, a lucky day may give a team a victory, but it would not be enough to guarantee a trophy. Consistency is key, after all.

League competitions are a way in which football structure would become a caste system, in opposition to a more democratic and horizontal way. This trend, with teams organising themselves into castes is nowadays not only limited to national borders. The recent attempt at organising a European Super League shows how the wealthiest clubs in the world are not shy in attempting to concentrate even more financial resources. The cup, however, gives supporters, who are used to being on the shadow of much wealthier teams, a glimpse of hope and joy. It also puts them closer, even if for a brief period of 90 minutes, to perhaps the most popular and followed institution in any given country: the first tier of male professional football.

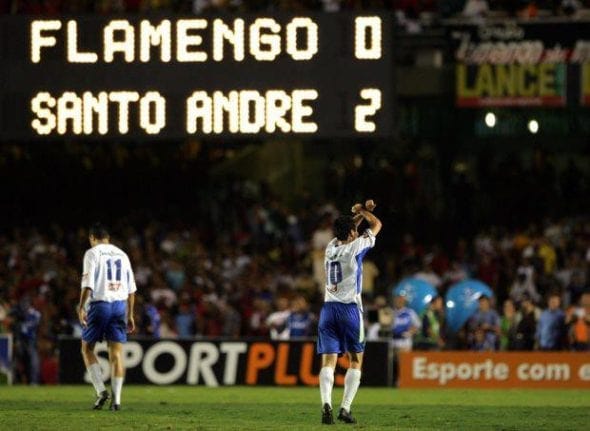

As a Brazilian and a Flamengo fan, infamously, in 2004, we lost a cup final in front of 80,000 fans against Santo André, currently in the 4th tier of Brazilian football. Our local rivals, Fluminense, would lose the very same cup final to another small team mere three years later. All other big teams in Brazil have an embarrassing story to tell from this competition, as they all have been eliminated at lowed ranking teams at some point over the 32 years the competition has been played.

It is, furthermore, in those upsets that the cup reveals its biggest strength: the mockery.

British anthropologist Radcliffe-Brown described, while conducting fieldwork in Africa, that there existed something which he called ‘joking relationships’. In the context of his ethnographic research, he described it as a type of ‘ritualised banter’ and identified two types: asymmetrical (in which the teased part were to not take offence) and symmetrical (in which both would make fun of each other). The former would arise from different social standings, as the latter would occur in more egalitarian standings. As a good, ol’ functionalist, Radcliffe-Brown affirmed that those relationships would help avoid any potential, violent conflicts by defusing any tension from escalating to something more violent. In essence, people would tease each other, so they would not hit each other. Meanwhile, those jokes would also ascertain a hierarchy.

The teasing, the mockery, the jokes! They are what make football a constant lived experience for fans all over the world! And in no place are they more alive and stronger than in the cups.

Playing in the 3rd tier of Swedish football, Torns IF made a name of itself through its humorous online presence on Twitter. Recently, they guested IFK Göteborg. Among tweets joking at their own expense and by playing with nationally recognisable stereotypes of Sweden’s second largest city, they also remembered how they would be playing in the lowest rankings of amateur football in 1994/1995, while their rivals would be topping a Champions League group with Barcelona, Manchester United and Galatasaray. Through local engagement and support, they would take themselves to Sweden’s 3rd tier, representing a small community of around 1,200. IFK Göteborg is still one of Sweden’s largest clubs, with more European trophies than PSG and Manchester City, for example. During ninety minutes, for Torns IF, however, they were the team to be beaten.

I remember watching Newcastle being eliminated by 4th tier Stevenage at the FA Cup. Besides the pitch invasion, and the massive party thrown by the supporters after the final whistle, I could not stop thinking that the day after would be tough for Newcastle fans…

Stevenage 3 x 1 Newcastle: Photo by Joshua Law

The mockery extends to the streets, pubs, companies, hospitals, and so on. For the young ones, it is a test of will. A result that hurts but will also strengthen their passion for their football, and with due time can be something they can themselves mock.

Those are the competitions that can bring shame to the big guys by the hands of the little ones. Winning, for the big team, is an obligation. Losing is the deviant expectation; the reason for shame. It is during a cup upset that young prepubescent boys and girls can experience the formative experience of being mocked by their peers because of football. Mockery, of course, is a rite of passage, one that binds you to your beloved football team more than anything else.

Smaller teams, with their small fanbase, inhabit a different dimension of the sport. The larger clubs, all over the world, have fans in all corners of any given country. It is not hard to find a Newcastle fan outside of Newcastle; it is, however, much harder to find a Stevenage fan outside of Stevenage. Chances are that the celebration by a large part of Stevenage fans included mocking the person they knew who supported Newcastle. Furthermore, everyone who supported a large team in England probably made of fun of their mate who happened to be a Newcastle fan. January 7th was not an easy day for them…

As the financial abyss between the haves and the have-nots; (and also between the haves of some countries, and the haves of others) has grown exponentially, it becomes much clearer that money is king and is able, through buying the best players, practically guarantee winning the league. The larger this gap, the less competitive the league is. Less rich teams often content themselves with just not being relegated. It leaves little place for the unexpected, which often is what makes us, humans, laugh.

It is in a national cup that a team can invert their position and subvert rational expectations. Cups offer subaltern teams a chance at glory, by offering a brief, yet powerful change of roles.

Aside from, for example, Leicester winning the Premier League in 2015/2016, very seldom can we witness a true surprising winner in a league competition. I do not mean that teams never perform better or worse than is expected of them by fans and journalists. Liverpool and Manchester United, England’s biggest rivals, have taken turns in out performing each other in the last ever since they were founded. Since the Premier League started, and thus the financial gap between the richer teams in the league, neither of them finished outside the top 10. Neither of them had a season with more losses than victories. Nor one with a negative goal difference. They are and have been, even at their worst, still one of the strongest teams in the country and in the world.

In a cup competition, however, there is a chance for them, and other big clubs, of being bested by opposition that is significantly poorer, less famous, with less money and less trophies. It brings back the element of chance that has been progressively lost to the overwhelming aspect of finances.

No amount of sportswashing from Middle Eastern dictatorships or Russian plutocrats can correct a bad ninety minutes, in a small stadium against a small, but fierce opposition. It has been the case since the beginning of the sport, and even if it may not remain as common as it once were, it is still a possibility. A small, low league team would need to spend millions in order to climb to the top of the pyramid. In a cup, they can, however, beat a larger competitor by will, grit and luck, creating moments that will echo through the decades.

Cups are also the only truly national competitions in most countries as they represent cities and regions which do not have a strong and competitive football tradition. In Brazil, the Northern region, which encompasses 45% of the country’s territory has no representative in the top tier of Brazilian division. Of the 20 participants, only 5 are not from the South and the Southern region of the country. As of now, only one of them is in the top 10 (Goiás, in 10th place). The Bundesliga has eighteen teams, with only two from Eastern Germany: RB Leipzig and Union Berlin. None of the sixteen teams in the Swedish top tier comes Norrland, one of the three landsdelar, the historical lands that make up the country1, and an area that comprises approximately 60% of the territory.

Looking at the teams that make up any country’s top tier division is a lesson in history and geography. They show quite clearly which cities and regions have been, throughout history, the centre of economic activity in any given country. There are exceptions, of course, as Berlin and Paris are not in themselves historical football cities, but by and large, most large clubs are based the most urbanised areas, which also tend to be the wealthiest ones. The rivalry between Liverpool and Manchester are a clear example of that. Munich, Rio de Janeiro, Madrid, Barcelona, São Paulo, Lisbon, Marseille, Milan, amongst others are known, not only by their clubs, but also by being, in different degrees, cultural and economical centres in their own countries.

They do not, however, hold the monopoly of the sport in their countries. In all countries in which football is a relevant social fact, it exists from the smallest villages to the largest cities. And more often than not, these places all have their football clubs. In Europe and South America, teams in the top tiers and the lower leagues can equally be more than a century old. Being a wealthier and successful team does not mean being more traditional. Notts County in the 5th tier of English football, and one of the first teams to win the F.A Cup were founded in 1862. Their rivals, two times European Champions and recently promoted to the Premier League, Nottingham Forest, in 1865. The F.A Cup, however, is where they can meet; it is the competition that potentially unites them.

And it is in the national cups that the teams from smaller cities and villages; the places without foreign tourists and internationally recognisable landmarks; the places were people just drive by, and are ignored even by the national media, along with the ugly ducklings of famous places are given a chance to be in the spotlight. It is where the large, inaccessibly professional teams are made to play in humble pitches, drawing the attention of a high percentage of the local population. It is where the stars, whose monthly wages sometimes are larger than the whole operational costs of their rivals for a whole year, are made flesh and blood, and face players who actually need to worry about the energy bill or the price of groceries. It is where highly-capitalistic football faces sees the absurdity of it all in comparison to, well, normal life. It is where giants can fall, even if they probably will not.

The cups are the high point of marginalised teams and marginalised athletes. As the stars are known throughout their country, they are merely the tip of the iceberg of professional football. In Brazil, 55% of football players make minimum wage. Only 12% make more than 5,000 reais (less than 1,000 US$). As the country pays attention to the top stars, a huge mass of unknown athletes make as much as any working class worker. Those athletes toil in the lower leagues. However, a local cup can give them a chance to be a part of the same universe of the stars they see in their television sets. Even if for a fleeting moment.

Cup matches can finance a small club for the rest of the year through ticket attendance and television rights. It can be the high point of a club for many, many years.

As contemporary football, with billionaire clubs, burns through piles of cash every season, one cannot forget that they are not the reality of the large majority of clubs. Clubs that do not rely on international fans and audience; that do not rely even on a national profile. Those are clubs are made by the blood, sweat and tears of poorly played players, voluntary workers, and dedicated fans. Those clubs are often an important centre both sociability and pride for small communities. They are the ones providing entertainment, building a sense of belonging. They are the ones that provide youth football, not for the sake of creating the next super star, but rather as a fun activity for children and teenagers.

It is through the national cups that those teams are allowed to dream, to soar higher than usual. By being allowed to do so, they offer us, a living example that, the extremely unlikely is absolutely not impossible.

Historically, it is actually four: Götaland, Svealand, Norrland and Österland. However, the fourth one is current day Finland.